The Holistic Paradigm as Democracy's Evolutionary Frontier

By Andy Paice

(part 1)

This year has been flying by and for many months now I’ve been meaning to put down some thinking that’s been brewing during my past six years working in the field of participatory and deliberative democracy. Finally I’m relieved to say here it is!

I’ve been incredibly fortunate in that what started out as a passion for facilitating community and activist gatherings eventually turned into professional associate work for the UK’s leading participation organisations.

It’s been fantastic to play a part in an exciting stage in the development of democracy, namely the emergence of citizens’ deliberation as a viable complement to our systems of representation. So far I’ve been involved in facilitating 14 citizens assemblies and juries around the UK, consulted on Austria’s national climate assembly and played a co-design role in the creation of a large number of hyper local community assemblies in the London Borough of Newham.

Whilst carrying out that work I’ve witnessed a great deal and had plenty of time to reflect on this pioneering field and form my own thoughts on its potential for further development. Now feels like an opportune moment to share thoughts and ideas that I, as a habitually discreet and reflective person, haven’t tended to vocalise or broadcast much, at least so far…

As quite a lot has been brewing I’ll touch upon a few themes in this piece and hopefully expand upon a few of them later in further articles.

For the past five years, I've been engaged in two streams of seemingly distinct pursuits.

Firstly the newly evolving field of participatory and deliberative democracy and secondly my longstanding inquiry into the fields of holism, consciousness, psychology, systems theory and spiritual and wisdom traditions. The spiritual inquiry has been a particularly strong personal theme - in the 90s and 00s I spent nearly a decade as a monastic in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

Despite their surface differences, I've sensed that holistic thinking has profound implications for the long term future of democracy. So while leading or facilitating deliberative forums on diverse topics such as climate change, the future of high streets or the cost of living crisis, I've also been contemplating the potential for these dimensions to inform each other.

Furthermore, my connection with colleagues from the Co-Intelligence Institute, founded by Tom Atlee, has provided a wonderful community to delve into these themes. Over the past thirty years Tom has been a pioneer in exploring the intersections of deliberative democracy, collaborative governance, and the holistic worldview.

So this article represents some of the maturation of all of the above. I’ve divided it into two parts. In part one I reflect on:

our dominant cultural paradigm and its destructive consequences

the fact that there’s an emerging, more holistic worldview that is more aligned with reality and therefore more able to address humanity’s crises.

the state of democracy in 2024 and a burgeoning field of democratic innovation

the indications that this field belongs to a new holistic cultural paradigm

In part two I delve into:

future developments that might be needed for governance and collective decision making to embrace these deeper realities

the projects involved in my work with the Co-Intelligence Institute to help catalyse a cultural shift

Our way of seeing

I’ve been following with keen interest thinkers, philosophers and scientists who suggest that the multiple intertwined crises we are facing are symptomatic of a deeper malaise. They all point towards the heart of the problem being the mental models in which we’re embedded, the dominant views or paradigms through which we see ourselves and the world.

Like fish swimming in water we are unaware of the deep conceptual structures that have shaped the world we’ve created. Systems thinker and scientist Donella Meadows proposed that the most impactful leverage point for changing a system is at the level of transcending paradigms - of being able to move beyond the stories we're telling ourselves about what's real and possible. However before we can transcend a paradigm we need to be able to see the one we’re currently swimming in. Complexity theorist and practitioner Nora Bateson asks "How do we think our way through the messes we’re in, when the way we think is part of the mess?" Similarly philosopher Bayo Akomolafe questions “What if the way we act, actually serves to reproduce the same conditions we are striving to escape?”

In that respect it’s important to get to know this dominant view which can be described in different ways, for example, as arising from modernity, from separation consciousness or the scientific Newtonian-Cartesian paradigm that formed as part of the Enlightenment.

The paradigm shift of modernity that began in 17th century Europe laid the cognitive foundations for the world we are living in today, how we perceive the natural world and our place in it. The world its scientists and philosophers describe is mechanistic and deterministic, a kind of a clockwork universe in which matter is fundamental and reductionist materialist science is the main tool for understanding reality.

On the one hand this form of thinking and seeing has enabled humanity to advance in a particular trajectory. It has helped build an industrial civilisation, given us the internet and advanced notions such as human rights and progress. On the other hand this worldview tells us we are all separate entities, separate from each other and the natural world.

Consequently it has given rise to a combative mindset that urges us to conquer, dominate and prevail over the hostile otherness of the world and other separate individuals.

Jeremy Lent explains this mental model as having roots in Cartesian concepts. 17th Century French philosopher Réné Descartes pronounced “cogito ergo sum” - I think, therefore I am. The human ability to think gives us an identity as something real and special whereas the rest of the natural world appears as unthinking and therefore lifeless, like parts in a big machine. The consequences of this worldview place humans at the top of a hierarchy with a separate natural world that is open to dominion and exploitation.

Jonathan Rowson directly links humanity’s current crises to the exhaustion of this worldview and calls it the Metacrisis: “the historically specific threat to truth, beauty, and goodness caused by our persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality. The metacrisis is the crisis within and between all the world’s major crises, a root cause that is at once singular and plural, a multi-faceted delusion arising from the spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity that permeates the world’s interrelated challenges and manifests institutionally and culturally to the detriment of life on earth.”

I share the conviction that our dominant culture, the one we bathe in that informs your and my thinking every day, has fundamentally misunderstood the nature of reality. This worldview is misaligned with the truth of all manifold things being part of an endless flow or process of interconnectedness and interdependence of incomprehensible complexity. It ignores that there is ultimately an intrinsic wholeness, a fundamental ground of being that interpenetrates all things.

Advances in science now suggest the universe teems with cooperative, symbiotic relationships, much more so than the dynamics of competition, combat and selfishness. So perhaps it is now our evolutionary task to align our social and economic systems with these deep realities and bring them into harmony with the natural world of which we are but a part, which is where my interest and practice in the world of democracy comes in…

Democracy in 2024

2024 is a particularly interesting year for democracy with 76 nations going to the polls, directly affecting over half of humanity. Yet we have to face it, democracy as a system of governance is in trouble. Everywhere we look, fewer and fewer people believe that our representative and electoral systems can deliver the kind of future they’d like to see. Strong man authoritarian regimes are on the rise, in the USA Democrats and Republicans can no longer even agree on basic voting procedures, global tech platforms create group-think echo chambers that promote mutually exclusive tribes and culture wars rage.

At a time when humanity faces deep existential crises that threaten our long term future (climate, biodiversity, proliferation of biological and nuclear weapons and more), common ground solutions are needed more than ever. And yet polarisation and short term thinking are increasing, hampering our ability at every level to work collectively on our biggest issues.

Perhaps that too is related to the modernist paradigm of separation and control in which our current democratic systems are embedded. Watch any political programme on television, observe any democratic debate (the word debate has its roots in the french de-battre - to beat down) or electioneering and you’ll see the logic of combat, where defeating the political opponent or party is paramount.

In the realm of electoral democracy monolithic packages of ideology and values - progressives vs conservatives, libertarians vs statists - vie for supremacy. Power changes hands and changes back again, rarely venturing beyond narrow short term goals, whilst the world staggers towards a horizon of depletion and destruction.

However, there are green shoots of something new emerging. In the field of democratic innovation I believe we are seeing a broader paradigm shift away from modernity (and in some respects postmodernity which has its own drawbacks in the rejection of any claims of truth or meaning) towards a wiser, more holistic way of decision making. It’s my conviction that the adoption of participatory, deliberative democracy and collaborative forms of governance are arising as a facet of an evolutionary trajectory towards greater holistic thinking. We’re living in times which compel us to evolve. Whether or not we manage to do that is another matter…

Does democratic innovation belong to a new paradigm?

It is hard to pin down and define this new paradigm due to its emergent nature - it is not yet fully formed or articulated. However, I would venture to say that it involves a more holistic worldview or way of seeing and understanding reality. It embraces interconnectedness, complexity, feedback effects and a recognition that our current fragmented and reductionist modes of thinking are insufficient for grappling with the multifaceted challenges we face.

So in what ways could the emerging field of democratic innovation be seen as embodying aspects of this emerging new, holistic paradigm?

Whereas the dominant modernity paradigm has seen the world as mechanistic, the emerging one appreciates the world’s complexity. Citizens’ Assemblies and Juries have appeared in the past few years as a way of embracing complexity and tackling entangled issues such as abortion rights, climate change, assisted dying, and hate crime.

For readers that aren’t familiar, Citizens’ Assemblies bring together a sample of randomly selected citizens that mirror the diversity of a population who listen to a variety of experts, stakeholders and people with lived experience on a given issue. They then deliberate for an extended period and finally come to collective conclusions and recommendations. This represents a leap towards holistic policy making, compared to decisions borne of political battle by a few elected representatives, their chosen advisors and the influence of opposing lobbyists.

Deliberative democracy brings multiple perspectives together (those of diverse citizens, experts, stakeholders, politicians, etc.). They work towards a whole system approach with participants acting as multiple sensors of reality coming together to deliberate, each of them seeing different aspects of the issue at hand which help move towards a fuller picture. Their final recommendations thus represent a greater degree of collective wisdom.

This demonstrates a collaborative form of democracy in that differences of opinion play a new role: they are seen less as problems to overcome (as we witness in zero sum party political battles) and more as diverse resources that inform choices.

Of course the success of citizens’ deliberation depends upon well designed and facilitated processes. Yet when the right ingredients are in place, common goals and shared orientation can be consistently reached (as seen in the outcomes of increasingly numerous assemblies and juries taking place across the globe). This shows the potential to evolve democracy beyond the realm of partisan politics towards governance based on collective sensemaking.

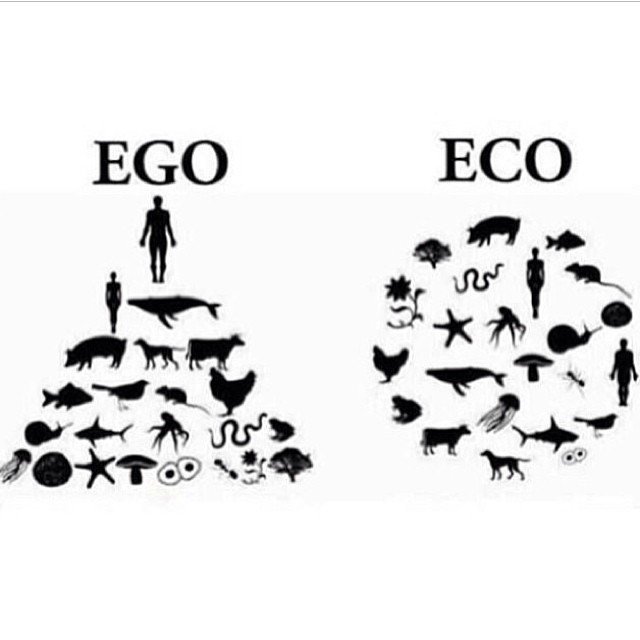

The decision by a representative or an institution of governance to convene a participatory forum demonstrates a shift of an ego-system approach to an ecosystem one. The ego based advocacy approach of ‘knowing what’s best’ for their constituents shifts towards a facilitative leadership approach that aims to listen to and engage an entire ecosystem of people and perspectives.

This approach demonstrates a potential (albeit not yet fully realised) to invert habitual power dynamics whereby a select few command the resources and decision making that the majority then live by. Selection processes like sortition recalibrate these imbalances towards empowering a truer representation of ‘the people’. For example the Global Assembly on Climate was a microcosm of the globe -“100 assembly members, proportionally representative of the world's population by gender, age, geography, attitude toward climate change, and educational level” - which meant the majority of participants were from poorer, less dominant nations in the Global South.

In general the participatory turn in democracy can be seen as having a deeply holistic significance. Namely that life exists as an interconnected web whereby the unique expression of every being contributes in some way to the wellbeing of the whole. That understanding calls each of us as individuals into honing and sharing our unique gifts and following our natural passion. Equally, this understanding highlights a need to design social systems so that they appreciate, evoke and engage every kind of diversity and uniqueness.

That kind of understanding can be seen shaping the participatory democracy of one of the most pioneering democratic nations: Taiwan. In the realm of digital affairs they have harnessed platforms such as Polis that help societies to understand issues in terms of both diverging perspectives and tribes of opinion as well as areas of consensus where there may be possibility for shared outcomes. Audrey Tang, the digital minister of Taiwan, is also a strong advocate for the notion of Plurality - cooperation across differences: “We believe we can create a more diverse, inclusive and prosperous society through collective brainstorming, respecting diverse viewpoints, and transcending boundaries…”

The book ‘Citizens’ by Jon Alexander argues that we are indeed moving through a participatory developmental trajectory, a shift from our past as ‘subjects who obeyed’, to our present as ‘consumers with choices’ to a future as ‘citizens with purpose and agency to create.’

New Citizenship Project

The concepts in the table to the left give an impression of the different narratives of who we are as humans that our societies are moving through. The red ‘consumer’ column broadly relates to the modernist paradigm whilst the blue ‘citizen’ column gives a sense of a more interconnected, interdependent, holistic paradigm.

A participatory shift would both require and call forth new structures and ways of co-creating. Are these new shoots of possibility in the field of democratic participation emerging as pointers towards a new more complex and interconnected order? Are we seeing a new paradigm emerge?

Paradigms take time to take hold. We are still living in the structures of the one which began four centuries ago. Do we have time to change as a planetary species? Will rapid destruction of our ecosystems force us to change or will humanity destroy itself? As far as I’m concerned it’s impossible to know. Yet in the field of participatory and deliberative democracy, I feel there is potential for a sea-change arising from holistic principles.

How we might deepen into such a paradigm shift in democracy will be the focus of part 2 of this article

Part 1 of this article explored the emergence of a new paradigm, a more holistic worldview aligned with reality, embracing interconnectedness and therefore better able to address humanity’s crises. It also highlighted the burgeoning field of democratic innovation and pointed out aspects that suggest this field is a facet of this new holistic paradigm.

If that is the case, how might we take democratic innovation into deeper levels of this shift so that it becomes ever more able to address our collective predicaments? That inquiry is the focus of part 2 of this article.

Building on recent successes

Presently, participatory and deliberative democracy methods are only minor features within the broader landscape of democracy. This landscape is primarily defined by entrenched opacity, a feeling of detachment from those in power, and sporadic citizen engagement limited to voting every few years.

Even where democratic innovations have been adopted there are still questions of the extent to which outcomes and recommendations are implemented or meaningfully shape policy. The development of effective, empowered participation is one of the first necessities towards creating, not just new ways of listening to people, but a thriving agentic democratic culture. We are still a long way from achieving that.

Nevertheless we can take encouragement in the fact that there is a burgeoning field, a wave of democratic innovation with hundreds of examples from around the world over the past few years. These recent successes show something big is shifting. A potential has opened that needs to be pursued if democracy is to embrace the complex realities and challenges of the future.

So far the field of democratic innovation has effectively demonstrated outcomes that have much greater democratic legitimacy due to the deeper involvement of the general public. Citizens’ participation convened using sortition (random stratified selection) gives everyone at least a chance of effectively contributing their voice to an issue. If, in addition, processes are linked to wider participation via digital democracy, the level of legitimacy is further increased. Greater legitimacy in turn provides a mandate for representatives to act.

Participatory processes such as citizens assemblies and juries also increase the possibility of empowering marginalised voices. This can be done by actively seeking input from less heard sections of the community, those that are directly impacted by an issue or making sure the selection criteria of the sortition actively promotes inclusion.

These are all fantastic developments. So now how do we build on them to broaden and deepen democracy?

Towards whole system governance

Some have suggested that rather than having citizens’ deliberation processes necessarily tied to local or national government sponsorship, linking them to an affiliated network of diverse stakeholders could be a more fruitful path to governance and have more chance of producing truly empowered participation. Iswe argue for this route to impact in their paper “Getting Real About Citizens’ Assemblies: A New Theory of Change for Citizens’ Assemblies”

A concrete example of this kind of whole system approach to governance that actively engages citizens and stakeholders can be seen in the Convention of the Future Armenian. This involved the establishment of an Affiliation Network, comprising journalists, civil society organisations, businesses, and influential individuals committed to supporting and implementing the convention's recommendations. Despite initial government reluctance to endorse the initiative, it gained significant visibility and support from various other institutions which ended up backing it and pledging to do their best to implement its recommendations.

Rooting in holism rather than progressivism

Some on the progressive side of politics have allied themselves with the growing movement of democratic innovation and Citizens Assemblies’ seeing this as the way forward, citing their likelihood to produce more radically progressive proposals than the usual political systems. I personally feel this is a hazardous lens through which to view them.

Our modern paradigm is built on partisan warfare and so the opportunity of democratic innovation is to take us beyond partisan thinking. Again here I feel the most appropriate framing for citizens’ deliberation is a holistic one that explores how we can integrate the perspectives of the whole (where whole refers to whole groups, communities, societies, whole ecosystems, biospheres, planet, etc.) and find outcomes that work, as much as possible, for the whole.

Democracy Next, an international organisation which is also “exploring the next democratic paradigm taking shape”, highlights this in a newsletter by saying “We do not want to see a world where Assemblies are supported by liberals and opposed by conservatives, or vice versa, which is why we stressed their non-partisan nature… …Assemblies are not about winning parties, losing parties, ratifying pre-determined policies, or ideological labels — they are a break from the dominant paradigm. Within Assemblies themselves, we find that most partisan labels quickly become irrelevant. Assembly Members move on to focus on the meat of the policy questions at hand.”

Deliberative democracy offers a route to transcend the current paradigm and move beyond factionalism and left-versus-right positioning towards a more non-partisan state of affairs reflecting the will, not of the parts (nor parties), but of the wholes. This is important, not only because democracy should be a social process where the greatest number feels included, but also because it can bring a whole ecology of demographic diversity and also a diversity of values, capacities, and perspectives to bear on a given issue.

Differences are natural and generative

For this to work well I believe deliberative process and facilitation needs to pay more attention to working with divergent perspectives and integrating differences to produce new, creative outcomes. This is particularly necessary given the increasingly polarised nature of politics and human life in general, now characterised by internet echo chambers and heated culture wars.

Important underpinnings for a wiser, more holistic democracy that moves beyond partisanship can be found in the work of contemporary philosopher Iain McGilchrist. In his recent opus “The Matter With Things” he draws on the insights of previous philosophers and scientists such as physicist C.S Peirce who states “A thing without oppositions ipso facto does not exist … existence lies in opposition.” McGilchrist also highlights the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who saw resistance and pulling in opposite directions as essential for creativity and harmonious outcomes, as seen in his following statement:

There is clearly tension between opposing perspectives - of individualism and collectivism, progressivism and conservatisindellm, statism and libertarianism. Yet, rather than seeing these tensions as a potential source of creativity and innovation, our democratic systems often oversimplify and collapse them into simplistic outcomes, which do not address complex realities. For example our elections and voting mechanisms such as referendums reduce diverse perspectives to simplistic binaries: winners, losers, leavers, remainers.

This oversimplification also manifests in subtler ways within citizens' deliberative processes. A typical Citizens' Assembly progresses through phases such as generating ideas, deliberating, examining trade-offs, prioritising ideas, drafting recommendations, and voting for ratification. This process is effective in many ways and a huge improvement on electoral democracy alone. However in my experience the process of arriving at a series of recommendations in a given time frame means points of contention or differences within an assembly are often glossed over.

While time constraints are always a concern in deliberative processes, prioritising the surfacing of differences and embracing the tension of opposition would, in my opinion, serve as a catalyst for generating more creative solutions, potentially even helping to transform some of the conflictual issues found in our societies.

Drawing upon specific facilitation methods such as Dynamic Facilitation and Deep Democracy Lewis Method that honour the tension of opposing views without collapsing or bypassing them, could be instrumental in this regard.

Dynamic Facilitation has been used in Assemblies and Citizens’ Councils in Austria and Germany to create a container where creative ideas can emerge to address and integrate what previously seemed like irreconcilable views. Facilitation practitioner and scholar Rosa Zubizarreta explores the possibilities of these facilitation methods in Supporting the Creative Potential of Divergent Perspectives.

The generation of collective wisdom can be seen as the process of drawing on multiple partial truths in order to create a fuller picture, or even a leap towards an appraisal of an issue at an entirely new level. Daniel Schmactenberger gives an example in this video Navigating reality: It’s all about perspective of how seemingly opposing perspectives can help us perceive a larger reality. He uses the analogy of two-dimensional creatures debating over the nature of a three-dimensional shape - a cylinder. The creatures in different planes see either a circle or a rectangle, both partially true but also wrong in that they are incomplete representations of the full reality of the cylinder.

Similarly building a complete picture of an issue requires looking at something from all angles and holding the prospect that what seems outlandish to us as a facilitator or process designer may hold important information. This in turn requires working with our own perspectival or political biases and I would argue an even greater inclusion and tolerance of controversial points of view within the assembly process.

Neutrality or Omni-partiality?

This also connects to the question of how participatory forums such as assemblies are set up and whether impartiality and neutrality is ever possible in their design and facilitation, given that biases are always present.

In my opinion neutrality, the stance of “not taking sides”, may not be possible, however an attitude of omni-partiality may be a useful guiding value for participatory process. Omni-partiality means "being in favour of and biased towards the success of everyone and the whole." It is a concept that comes from the field of mediation and was coined by Kenneth Cloke (who in this video elaborates its meaning.)

Cloke regards the concept of neutrality having its origins in legal systems where a judge remains “distant from both sides, personally withdrawn, logical, emotionally unavailable, affectless - on nobody's side until the moment of decision and judgement.” Omni-partiality is about “becoming equally biased” towards all parties in a discussion or conflict. It goes beyond merely eliciting people’s positions or arguments and involves being emotionally available and connected to all parties, recognising the underlying interests and human experiences that may have shaped their positions.

Insights from the realm of inner and self psychological inquiry have personally served me in the practical application of omni-partiality when I am facilitating. In particular the notions of ‘subpersonalities’ and ‘shadow work’ which recognise that individuals possess a diverse array of inner voices or personas, a multitude of selves, voices, desires, and motivations, rather than being a monolithic, unified entity.

Different selves or roles become prominent and occupy the driver's seat of the psyche in response to individuals’ various life experiences, relationships, contexts and challenges. Conversely, disowned subpersonalities are parts that have been excluded from our lives. We suppress them due to association with painful experiences - for example growing up in a household where the adults display only tough, aggressive behaviours make it likely that a child will find it hard to own their vulnerability.

Carl Jung called the suppressed, disowned parts “the shadow”, parts which nevertheless remain active in the subconscious. One of the ways we can detect a shadow aspect of ourselves is when we notice ourselves feeling uncomfortable in the presence of or judging another person who turns out to be displaying the very qualities we have buried.

In the realm of democracy and politics I believe this understanding has huge importance. In legislatures and media we see politicians in ferocious and angry exchanges revolving around polarised ways of seeing: individual rights vs collective responsibility, safety vs freedom. In psychological terms they are theatres of warring subpersonalities. The way forward is reintegration, accepting and re-owning the opposing disowned energy or way of seeing in oneself. The result in terms of politics are more nuanced, wiser positions that integrate multiple truths.

The implications for deliberative democracy are significant and underappreciated. When designing a process, we can ask ourselves - who are the disowned voices (e.g for progressives, libertarians or conservatives) and how can we include them? When we’re facilitating and we notice ourselves feeling uncomfortable as a participant expresses views that we don’t agree with, simply knowing that this may be triggering our shadow can help us to ensure their perspectives are included. Of course this doesn’t mean having to adopt their position but does mean being able to connect with the human being and their underlying reasoning, interests and concerns.

This is a very practical way of working with our biases and moving towards omni-partiality.

Image created by prompt to Designer AI

Arnold Mindell, the originator of Process Work and Deep Democracy describes the phenomenon in the following terms: “the facilitator remembers that the various parts and people are ‘roles’. She remembers she can dream about these roles as if they were all inside herself. The ‘other’ and each role is a part of herself! She realizes that all the various parts in a conflict or discussion are actually roles that everyone has within themselves to a lesser or greater extent… that the ‘other’ is a role, a role that must be played out for it belongs not only to the ‘other’, but to all of us…”

Such insights are not necessarily new. Wisdom traditions from around the world throughout the ages have communicated that we are not isolated, separate entities, that we are in fact deeply interconnected and interdependent. As the Nobel Peace prize winning Zen Master Thich-Nhat Hanh wrote "Nothing can exist by itself alone. It has to depend on every other thing. That is called inter-being... There is no being; there is only inter-being."

Similarly in the Ubuntu philosophy of southern Africa, the pithy aphorism "I am because you are" captures the essence that our personal identities are inextricably interwoven, our sense of self is shaped by relationships with others. Ubuntu calls us to a participatory vision of community not just with our human family, but with the more-than-human world that sustains all life.

Myriad indigenous ways of being see all things as radically interconnected and suffused with sacred presence. Animate landscapes teem with subjectivities and intelligences - to be consulted and granted representation as partners in a broad democracy of being. What would democracy and deliberative democracy look like if we oriented it around the depth of these insights?

Ego to Eco

Contemporary thinker, Otto Scharmer of the Presencing Institute advocates for the shift from “Ego-systems” based in separation and competition dynamics to an “Eco-system” awareness based, collective action approach to economics, education and governance. In terms of democracy he advocates shifting the source of power from centralised ruler-centric or bureaucratic systems to “the real needs and aspirations of communities” via “a shared process of co-sensing and co-shaping the new.''

Democratic innovation has already started to show a way forward to move away from Ego-system politics. The ego-system approach is characterised by competing representatives who prioritise telling rather than listening to others, and whose interests are often beholden to narrow, interest groups.

In contrast, deliberative and participatory approaches call upon a whole host of inputs and voices for collaborative sensemaking and decision making.

To move even more deeply into an Eco-system approach we also need to reconsider our role as humans within this system. Our mental models, shaped by modernity, see humans as separate from and yet having dominion over nature, which is treated as having no other function than to serve us. This paradigm is one of hubris rendering us kings, standing on top of a pyramid, surveying everything seemingly below us.

The recent book “Ways of Being” by James Bridle urges us to reassess our assumptions. In an exploration of new scientific discoveries that show this planet to be in fact teeming with intelligences we barely understand, Bridle enlarges the definition of nature to include the arrival of advanced AI and machine intelligence and states:

“A new Copernican trauma looms, wherein we find ourselves standing on a ruined planet, not smart enough to save ourselves, and no longer by any stretch of the imagination the smartest living things around. Our very survival depends upon our ability to make a new compact with the more than human world, one which views the intelligence, the innate being, of all things - animal, vegetable and machine - not as another indication of our own superiority, but as an intimation of our ultimate interdependence, and as an urgent call to humility and care.”

This reality compels us to evolve beyond our current democratic paradigm characterised by Abraham Lincoln’s celebrated "Government of the people, by the people, for the people" in his Gettysburg Address. It urges us to align with Indigenous wisdom that sees animals, plants, mountains and rivers, unborn future generations as people and to work to include them in our democratic processes. In fact, it urges us to develop governance of, by and for the Whole.

In their RadicleCivics project Indy Johar and Fang Jui Chang have documented recent advances in this ego to eco transition: rivers have been granted legal personhood status, direct political representation of a sea is being made possible by an array of innovative listening exercises in the Embassy of the North Sea project and future generations gain a voice and agency through participatory processes that invite citizens into embodying the views of future citizens.

Further experimentation is required to incorporate the representation of more than human voices in democratic innovation and decision making via role play, field visits, video making, systemic constellations and advances in scientific research which are decoding animal communication using artificial intelligence.

The advance of Artificial Intelligence will clearly also have huge impacts on human society in the years to come and this too is a field where research is taking place with regards its potential for supporting deliberative democracy.

In any case the vision of citizens' assemblies transitioning towards forums in which an ecosystem of multiple intelligences from the human, non-human and more than human world gain agency and voice, assisted by technology to help understand, aggregate and find points of consensus is a fascinating and incredibly enlivening prospect.

Transformative Social Systems

I was recently introduced by Rosa Zubizarreta to a paper that has put forward a concept for bringing a whole ecosystem of practices under a unifying term, namely Transformative Social Systems (TSS).

The authors Laureen Golden and Pascale Mompoint-Gaillard describe a whole array of “practices, methods, procedures, and techniques that propose a different way of being and working together - a return to honoring what is meaningful, connected, life-enriching and joyful. TSS help us improve towards a greater sense of wholeness, well-being and life-affirming ways of being.”

The paper’s call to action is for practitioners of these methods to move beyond operating in silos towards greater interoperability and the cohering of a “movement of movements.” A space of mutual learning would help TSS become a more recognised field, ultimately supporting policymakers and administrators to include TSS in their decision making processes, potentially via participatory public engagements.

Image from the TSS paper

When I started writing this article (in part 1), I described my passion for the newly evolving field of participatory and deliberative democracy and my longstanding inquiry into the fields of holism, consciousness, psychology, systems theory and spiritual and wisdom traditions.

So the discovery of Transformative Social Systems resonates deeply with me, as it presents a unifying framework to bring together the various holistic practices and methodologies that I have been exploring.

Grounding democracy in wisdom

As we saw earlier in this article participatory and deliberative processes are advancing democracy towards enhanced legitimacy and social justice. From my perspective, these processes should build upon those foundations to also be recognized as platforms that serve perhaps an even more crucial role: that of fostering collective wisdom.

Currently, the connection between "wisdom" and "democracy" is rarely emphasised or explored. I am part of a team at the Co-Intelligence Institute (CII) aiming to change this perception and establish a meaningful relationship between these concepts. For many, the term 'wisdom' may seem abstract, elusive, or overly subjective. The Co-Intelligence Institute defines 'wisdom' as the ability to consider and act on what’s needed to generate long-term broad benefit.

The protocols of democratic affairs in our current dominant paradigm are grounded in the concept of due process. In other words, if you go through specific steps of a democratic process (such as majoritarian voting or a deliberative assembly selected by sortition and stratification) the outcome that results is deemed democratic. The reasoning is that fair and impartial procedures produce a legitimate result.

That humanity has evolved beyond autocracy is a cause for celebration, however it is still possible to follow the legitimate processes of our current representative systems and still end up with the results creating (or failing to prevent) collective catastrophe. Avoiding catastrophe means the outcomes of our democratic processes need to be aligned with addressing realities, rather than merely following our current standards of legitimacy. Our processes need to embrace more of reality than the narrow interests that tend to dominate our current systems.

CII is specifically focused on an ongoing investigation into "wise democracy," which we define as “democracy of, by and for the whole” – i.e. arising from and benefiting the whole.

This framing prompts an exploration that both includes and moves beyond notions of fairness of process towards what it means to seek and generate actionable collective wisdom through democratic processes, an area often overlooked in conventional representative and deliberative democracy frameworks.

From this perspective the protocols would be: if you set up processes, conditions, embed assumptions, agreements, so that “The whole system is able to manage the affairs of the whole system for long term broad benefit” (where the whole includes human, more than humans, future generations, the whole planet) that will be a new kind of legitimacy that has the capacity to move us towards a sustainable future.

Tom Atlee, the founder of CII, from 2002 shares a vision of what future democracy could be in this poetic form:

Navigating limitations

Everything discussed until now represents the vision and potential areas to move into. Yet this would be incomplete without a sincere assessment of the huge challenges involved in actualising these holistic principles within democratic processes and governance systems.

For a start even though governments and institutions are increasingly willing to trust and try out participatory forums like citizens’ assemblies, they are far from a mainstream practice and in most countries have a low public profile. Deliberative democracy methods are currently making a small impact and what I’ve described in this article represents potential innovation on top of what is already considered cutting-edge democratic reform. Designing governance systems from a holistic paradigm involves the challenge of pushing the boundaries even further.

Our governments, bureaucracies, and political processes have developed over centuries shaped by the dominant modernist worldview. This has enabled important advances like elected representation, constitutional checks on power, and the rule of law. However, assumptions about how democracy should function (such as oppositional campaigning, lobbying and majority-rule decision-making) are hardwired into the design of current structures, procedures, and cultural norms.

So the room for manoeuvre in innovating new forms of sensemaking into collective forums like assemblies is limited and, in some respects, with good reason. Attempting to redesign these systems around holistic principles like ecocentrism, synergy and collective wisdom is likely to face institutional inertia or opposition. Understandable resistance may also come from those currently working hard to establish the field of deliberative and participatory democracy. They may perceive the innovations described as potentially destabilising, undermining a willingness from institutions to embed and implement these processes.

For many in the general public or the field of democracy, some or all of the ideas proposed here may seem a bit ‘out there’ involving concepts or practices that may appear eccentric or fringe. I acknowledge that! And I also hold the conviction that these times are impelling us towards new thinking and experimentation. New paradigms by their nature will always appear as something strange and threatening. Consider this - democratic revolutions sparked by modern reason centuries ago initially struck the feudal mentality as dangerous fringe thinking.

Yet, even those of us committed to paving the way for a new holistic paradigm, in democracy or elsewhere, must confront the reality that we too have been conditioned by prevailing worldviews. I know that I have my own unconscious biases, ingrained patterns of thinking, and blind spots rooted in dominant narratives that permeate my own ways of being. From my point of view, embodying a holistic worldview that honours the interconnectedness of all life is an ongoing journey. It demands self-inquiry, a genuine openness to diverse perspectives, and a willingness to reevaluate assumptions.

All feedback to this article is therefore welcome!

Practical Ways Forward

For those inspired by the vision outlined, here are some concrete pathways for transforming these possibilities into lived realities:

First is a need to reframe our shared cultural narratives of what is and what’s possible. Education, storytelling and thought leadership for a paradigm shift play an important role here. Many of the thinkers highlighted in this article are doing just that. In Occupying the New Paradigm Rosa Zubizarreta advocates making support for this way of seeing and being more visible, being vulnerable about our own conditionings, and cultivating solidarity as ways to help "occupy" and transition to a new holistic paradigm.

Secondly we have to bring practitioners, innovators and thinkers together for cross-pollinating insights and developing shareable tools and methodologies. Collaboration amongst practitioners of Transformational Social Systems and exchange between democracy innovators and TSS practitioners would help to develop holistic methodologies so that they may be more easily integrated into democratic processes.

And lastly the vision implores us to experiment with new ways of doing holistic democracy and governance.

I’m part of a team in the Co-Intelligence Institute involved in bringing these pathways to life via a series of projects.

Through transformational storytelling, CII showcases inspiring examples of wise democracy and holistic governance already blossoming around the world. We’ve been convening spaces for practitioners to share insights, including regular community calls, to deepen praxis around evoking collective wisdom and the design of dialogical processes.

Tom Atlee and Martin Rausch have also put together the formidable Wise Democracy Pattern Language of design elements (many of them grounded in deliberative and dialogical principles) drawn from real-life innovations, to help re-imagine and transform the ways we manage our collective decisions and our shared world.

We’re continually researching and exploring possibilities with people working in the realm of collective wisdom and democratic innovation.

The need for bold experimentation at the edge of where democratic innovation lies today is close to my heart. To address the challenges I’ve outlined, holistic principles should be prototyped and iterated through experimentation and methods cross-fertilised in low-risk civic contexts or outside formal systems first. As successful examples gradually earn legitimacy, they can then be adopted gradually into democratic cultures.

So this is exactly the kind of experimentation I am currently working towards. I look forward to sharing more details on what such action research might look like. If you have ideas in this domain that resonate with what you’ve read here or you have thoughts on funding opportunities please get in touch.

Our choice, as always, is to regress into degeneration or evolve!

+++++

To recap - Part 1 explored the emergence of a new paradigm, a more holistic worldview aligned with reality, embracing interconnectedness and therefore better able to address humanity’s crises. It also highlighted the burgeoning field of democratic innovation and pointed out aspects that suggest this field is a facet of this new holistic paradigm.

In part 2 I explore - how might we take democratic innovation into deeper levels of this shift so that it becomes ever more able to address our collective predicaments?

Inspiration, case studies, and ideas inspired here by Iswe Foundation DemocracyNext Rosa Zubizarreta Dr Iain McGilchrist Daniel Schmactenberger Arnold Mindell Otto Scharmer James Bridle Fang-Jui Chang Indy Johar Pascale Mompoint-Gaillard Laureen Golden Tom Atlee Martin Rausch Co-Intelligence Institute

Also Rosa Zubizarreta has just published "Occupy the New Paradigm" which is a great complement to this article and explores similar themes. She advocates making support for this way of seeing and being more visible, being vulnerable about our own conditionings, and cultivating solidarity as ways to help "occupy" and transition to a new holistic paradigm https://lnkd.in/e8KA3fS5

Acknowledgments

A huge thank you to Tom Atlee and Rosa Zubizarreta not only for their feedback and suggested edits but also for their own profound work which has directly inspired many of the ideas presented in this article.

Thank you Natalia Rogovin for your astute comments, edit suggestions and questions that helped me enormously.

Gratitude to colleagues and friends in the field of deliberative democracy particularly at Shared Future CIC , MutualGain Ltd and Involve

And a big shout out for the inspiration provided by all the thinkers, philosophers, scientists, psychologists, scholars and democracy practitioners mentioned in both parts of this article.

Recognition also to the non-human assistance of Artificial Intelligence (Claude AI and ChatGPT) in highlighting elements I might be missing and formulating some of my writing. …